On an interdisciplinary expedition from Greenland to the Canadian Arctic, Pamela EA gathered 10 words connecting the Arctic with the rest of the planet.

Texts by Pamela EA and Hailey Basiouny

The project was supported by The Explorers Club and Adventure Canada.

Qujannamiik to Cedar Swan, Stefan Kindberg, Milbry Polk, Kaleigh Potts, Alana Bradley-Swan, Alexis Saulnier, Dr. J. Sherman Boates, Dr. Lauren Erland, Jason Edmunds, John Blyth, Joseph Frey, Julie Bernier, Looee Okalik, Maeva Esteva and Robin Houlik. Special thanks to Alex Jardine, Biinia Chemnitz Frederiksen, Dr. Marc St-Onge, Kaylee Baxter, Margaret Atwood, Steve Burrows, Robin Houlik and Wayne Broomfieldu for taking the time to spark meaningful dialogue.

November 12, 2024

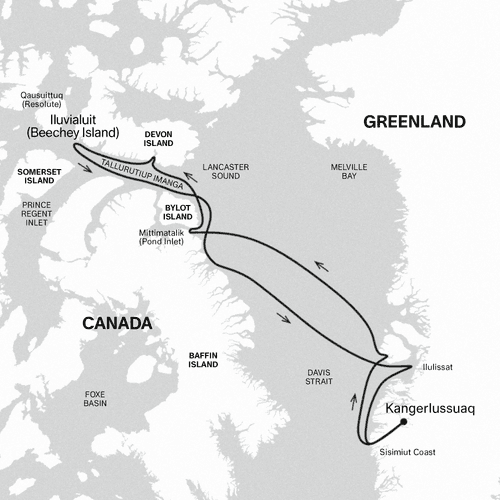

Route map for the High Arctic Explorer Expedition from Kangerlussuaq to Iluvialuit. Greenland and Arctic Canada, 2024

The Davis Strait, located north of the Labrador Sea, is the southern arm of the Arctic Ocean. It has long facilitated exploration, maritime trade, scientific research, and cultural exchange.

Navigating the strait from Kangerlussuaq to Iluvialuit (Beechey Island) aboard the High Arctic Explorer, alongside Inuit cultural educators, scientists, historians, and artists—with the support of The Explorers Club and Adventure Canada—felt like a significant leap into a new era of exploration. One where individuals are no longer competing to be the "first to” achieve something, but are instead collaborating toward conservation and dialogue to drive meaningful action for environmental protection.

A core aim of this expedition has been to document interdisciplinary conversations with experts on board to raise awareness around the effects of global heating on the region, and the Arctic’s interconnectedness to the rest of the world. Through a series of conversations, we sought to bridge the gap between the Arctic and the global climate discourse.

Viewed as the “last frontier”, disconnected from the lives of most, although the region might seem distant, what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. The region’s health or decline as a consequence of a changing climate has ripple effects that reach every corner of the planet.

This summer alone the temperature was 2.25 F (1.25 C) higher than the average summer. In many ways, the Arctic is acting as the proverbial canary in the coal mine, sounding the alarm bells for the threat of an unstable climate fueled by wreckless greenhouse gas emissions as damaging byproducts of the fossil fuel industry. The "Two Degrees is Too High" report shows that even 2°C of global warming could lead to irreversible damage to Earth's frozen regions, melting ice sheets, glaciers, sea ice, permafrost, and more, with devastating impacts on people, nature, and societies worldwide.

Adventure Canada expedition team landing at Iluvialuit (Beechey Island), 2024. Photography by Pamela EA

The Arctic may be beyond the reach of many of us, but it is never beyond our influence. Our planet’s northern polar region, the Arctic encompasses the Arctic Ocean and swaths of the surrounding land masses. There, a complex web of relationships has survived, evolved, and adapted to sustain a dynamic ecological environment—but it is increasingly difficult to adapt in response to accelerating climate change.

Home to rich ecological diversity, the Arctic is a landscape of vast boreal forests, dense populations of birds, fish, large land mammals like grizzly bears and caribou, and marine mammals such as belugas and narwhals.5 The fate of many of these species hangs in the balance, as this region has been warming twice as fast as the rest of the Earth.6

Today almost four million people, including more than 40 Indigenous groups, live in the Arctic. Not only adapting to a changing climate, Arctic residents are also finding new ways to preserve their customs, languages, and traditions. With resilience and a demonstrated ability to collaborate regionally, their voices are vital in understanding and addressing the challenges posed by climate change.7 Like elsewhere in the world, communities that contribute the least to global warming and serve as an example of thoughtful living with “nature” (of which we are part) are suffering the most.

Rapidly melting, 95% of the Arctic’s oldest and thickest sea ice cover has already been lost.8 Snow and ice are widely used in traditional Intuit medicine, both for healing and as ritual and ceremony. Communities and scientists affirm that the Arctic has come to serve as a storage place for the world’s pollutants.

Loss of sea ice, the landscape’s snow and ice, and accumulation of contaminants there harm local wildlife and Indigenous communities, and weaken the region’s ability to support the entire planet in cooling down and restoring balance to our climate.9 Simply put: less snow and ice, less reflection of the sun’s energy back into space.

Sheila Watt-Cloutier, a Canadian Inuk activist, explains: “…the cold, the ice, and snow…that is our life force. It isn’t just about the ice itself, it’s what the ice represents.”10 She, and the communities and geographies of the Arctic, reveal just how unremote the Arctic is. What do we want to represent for the Arctic, a frontline in our fight for the planet?

Image by Louisa Belk at the Arctic Trivia Night & Zine Launch at Arc'teryx New York

Get your copy of "Arctic Words from Kangerlussuaq to Inuvialuit" at climatewords.org/shop.

We use cookies to analyze site usage and enhance navigation. By accepting, you agree to our use of cookies. Accept

Subscribe to our newsletter and be the first to get news on climate literacy!

By submitting I confirm that I have read Climate Words’ privacy policy and agree that Climate Words may send me announcements to the email address entered above and that my data will be processed for this purpose in accordance with Climate Words’ privacy policy.